Will the Real Anti-Monopolists Please Stand Up?

On Abundance and Antitrust

It has been striking over the last couple of weeks to see so many people who identify as anti-monopolists lash out at Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s Abundance. Part of what is going on is that they want blaming business to be a core part of the Democratic Party’s intellectual framework and so they were never going to take kindly to analysis that did anything other than that. Another part is that anti-business instincts ran fairly strong in parts of the Democratic Party during the Biden era (remember “greedflation”) and they are afraid that may be waning.

You can find examples of it here, here, and here. Alex Bronzini-Vender assumes that abundance is in opposition to antitrust. So does the American Prospect. Zephyr Teachout was milder but also usefully asked “whether there is room within abundance for anti-monopoly politics.” For his part, Jeff Hauser of the Revolving Door Project echoed these arguments and put out this challenge.

Ok Jeff. I’m one of the proponents of the Abundance Agenda, a self-avowedly pro-market center-left Democrat, and I’m happy to have this debate. Here’s my central contention: across a wide variety of issue areas, a supply-oriented politics that focuses on abundance and bringing down the cost of living will do more to increase competition than the anti-business politics favored by Abundance’s critics from the left. Moreover, people who brand themselves anti-monopolists have been quite selective and narrow in which kinds of competition problems they actually promote more competition in.

In short, Abundance is the real anti-monopoly position.

Competition Affects Where We Live and How We Work

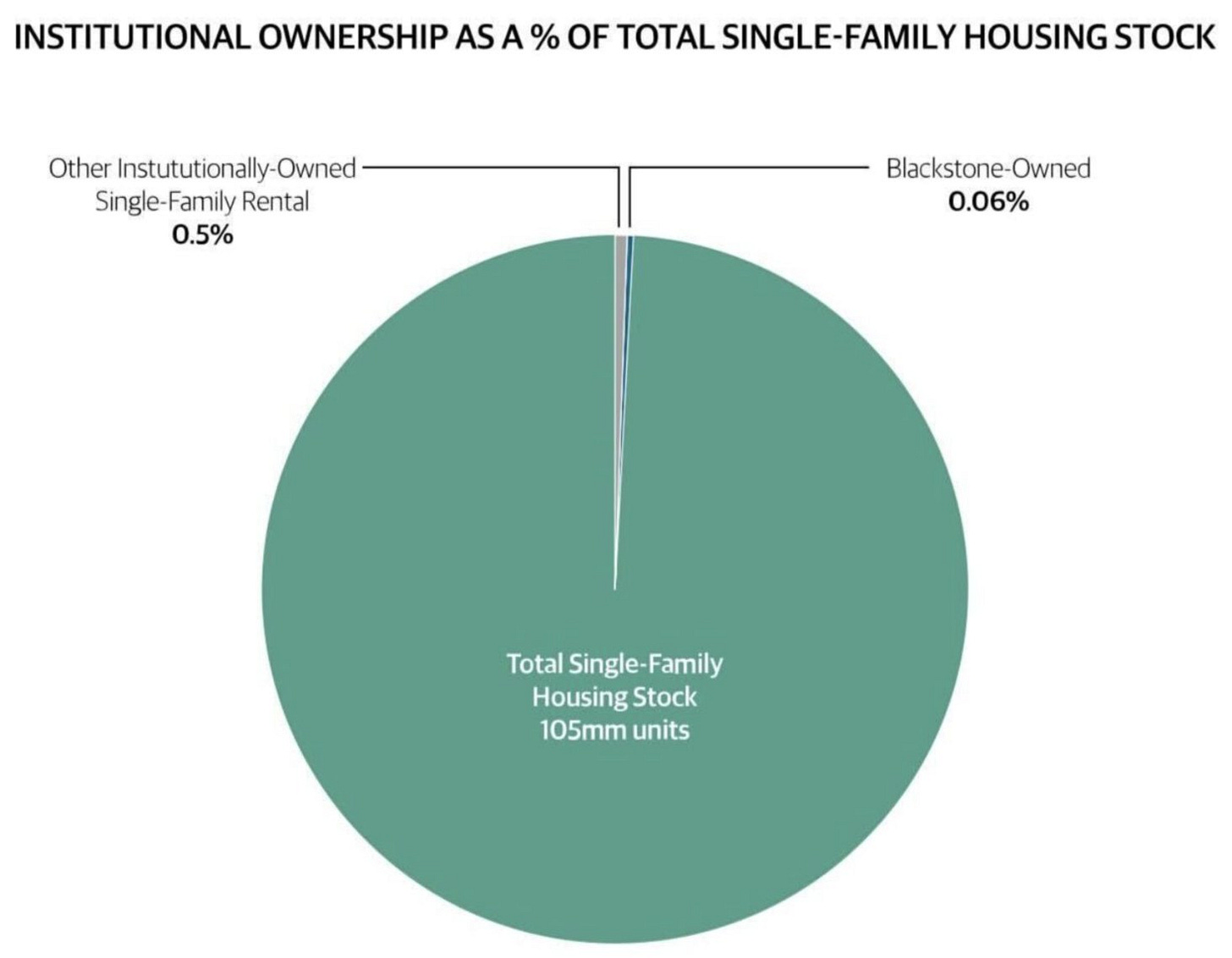

Let’s start with housing. When a developer builds new housing, that is more competition for landlords and incumbent property owners. With a sufficient housing supply, they have to compete to find a tenant or buyer rather than the renters and home buyers being held hostage by the market power of the landlord/incumbent. It is that issue, not the other scapegoats, that is the problem. Institutional investors, for example, own a tiny fraction of houses in this country.

In a similar vein, the biggest estimate of the impact of RealPage, an algorithmic rent-setting software that some have alleged allows landlords to collude, is $25 a month per unit. Collusion is bad and if RealPage and/or its users are found to have violated the law, they should be prosecuted, but $25 a month is a quite small fraction of the cost difference between the places that build and the places that do not. And you can see this in how people are voting with their feet. People are leaving blue states for red states and the biggest reason is housing costs and those cost differences are way more than $25 a month.

Increasing the housing supply via zoning reform is going to do a lot more for homebuyers and renters than scapegoating RealPage or AirBnB or institutional investors. The ultimate enemy of the renter is the invisible graveyard of housing that developers would like to have built but were not allowed to. It is scarcity that gives landlords power to charge high rents.

Not only that but, as Jerusalem Demsas notes, excessive zoning regulation disproportionately hurts smaller developers. So there’s that angle to it too.

Meanwhile, when homebuilders can buy foreign lumber more easily, that creates competition in their input goods and drives prices, which translates into more housing supply, i.e. more competition. On top of its other benefits, the case for free trade is a pro-competition, anti-monopoly case. Unfortunately, some people who brand themselves as anti-monopoly are also anti-trade.

Want to see monopoly power in action? Look at occupational licensing. These aren't just reasonable safety rules - they're legal barriers to entry that protect incumbents from competition. When states heavily fine people, in this case a military spouse, for giving diet advice without a license, that's not consumer protection - it's market exclusion. When licensing boards of existing practitioners decide who gets to compete with them, that's not oversight - it's cartel behavior. When licenses don't transfer across state lines despite identical safety standards, that's pure protectionism.

The real anti-monopoly position is clear: slash unnecessary licensing requirements, implement interstate recognition, and limit boards' ability to block competition. This doesn't mean eliminating all licensing - just the requirements that serve no purpose beyond protecting incumbents from healthy competition.

Monopolies By Sea, Air, and Land

That anti-trade instinct also chokes competition in shipping. The Jones Act prevents businesses who want to do domestic shipping from using foreign-owned or foreign-built or foreign-crewed vessels. This isn't about protecting American workers - it's about protecting a handful of American shipping companies from competition. If a manufacturer in Duluth Minnesota can't hire a foreign vessel to ship goods to Cleveland Ohio via the Great Lakes, that's not patriotism, that's a government-enforced monopoly.

Repealing the Jones Act would allow foreign vessels to compete on American waterways, dramatically reducing shipping costs and increasing options for American businesses. This would reduce prices for consumers, make American manufacturing more competitive by lowering input costs, reduce carbon emissions by shifting freight from trucks to more efficient water transport. Unfortunately, some self-proclaimed anti-monopolists want to keep the Jones Act in place. But true anti-monopoly politics means tearing down barriers to entry, not building walls to protect incumbents. Jones Act repeal is abundance politics in action - more ships, more competition, lower prices.

Let’s talk about airlines. Want to know why you can fly low-cost carriers like Ryanair in the EU but not the United States. It's the absurd cabotage rules that ban foreign airlines from competing on domestic routes. These rules effectively hand American airlines a government-protected monopoly over domestic air travel. If EasyJet could fly routes between U.S. cities, American carriers would face more competition on service quality and price. Suddenly, those baggage fees and cramped seats would face more market discipline. U.S. airlines would have to compete or lose customers. The real anti-monopoly position is clear: tear down these regulatory walls. Let foreign carriers compete.

Here’s another area where excessive regulatory barriers choke competition: car dealerships. In most states, it's illegal for auto manufacturers to sell directly to consumers. Why? Because car dealers have lobbied state legislatures to outlaw competition. This dealer franchise system is a pure middleman that serves no real purpose. Direct-to-consumer auto sales would revolutionize this broken market. Fixed pricing eliminates haggling. Online buying eliminates high-pressure sales tactics. Customers save thousands by cutting out the middleman. True anti-monopoly politics means ending these protectionist laws that do nothing but shield dealerships from competition.

Speaking of cars, the taxi medallion system was perhaps America's most visible anti-competitive system. Artificial scarcity drove medallion prices to over $1 million in NYC while passengers endured poor service, discriminatory pickup practices, and fixed pricing.

When Uber and Lyft entered the market, they shattered this government-enforced cartel overnight. The result? More drivers earned income, more passengers got rides, waiting times plummeted, service improved, prices became dynamic but generally lower, consumer surplus increased, and underserved neighborhoods had better access to transportation. And autonomous vehicles could end up providing even more competition in the transportation space.

True anti-monopoly politics means welcoming this kind of disruptive competition that improves service, expands access, and creates opportunity while breaking entrenched incumbents' chokehold on markets.

Competition Affects How We Take Care of Ourselves

Let’s talk about healthcare. The residency cap creates artificial scarcity, i.e. less competition, in the delivery of medical services, which results in higher prices. Excessively tight scope of practice laws for nurse practitioners and physician assistants do the same. In states where nurse practitioners can practice independently, patients see shorter wait times, lower costs, and no reduction in quality. That's what competition delivers. The real anti-monopoly position is to scrap the residency cap and expand scope-of-practice and then take it a step further by allowing foreign trained doctors to provide care under supervision, as eight states already do.

Certificate of Need laws are perhaps the most blatant example of anti-competitive regulation masquerading as consumer protection. They're literally designed to prevent new healthcare providers from entering markets unless they can prove "need"—with incumbent providers sitting on the approval boards and allowed to object to applications. This isn't theoretical. States with CON laws have 30% fewer rural hospitals, 13% fewer rural surgical centers, and 20% fewer psychiatric facilities than states without them. They have higher costs across multiple healthcare services. Of 83 statistical tests on CON laws and service availability, 78% found these laws reduce access to services.

When hospital executives can legally block competitors from opening facilities in their service area, that's not healthcare policy—it's government-sanctioned monopoly protection. The evidence is overwhelming that CON laws raise prices, limit access, and worsen outcomes. Repealing them would unleash competition in healthcare markets, particularly in underserved rural areas. True anti-monopoly politics means dismantling these regulatory barriers that protect incumbents from competitive pressure.

Or we could talk about baby formula. America's baby formula market is a textbook example of how regulations create monopolies while pretending to protect consumers. Three companies - Abbott, Reckitt, and Nestlé - control 90% of the market, not because they make superior products, but because FDA rules make it nearly impossible for new entrants to compete. Even worse, these rules block imports of European formula that many parents actually prefer and that has more up-to-date nutritional standards around DHA and added sugars. This regulatory capture is why a single plant shutdown in Michigan created a national crisis where parents couldn't feed their babies.

True anti-monopoly politics would eliminate the 25% tariffs on imported formula, recognize EU safety standards, update our 1980s-era regulations, and restructure WIC contracts to stop reinforcing monopoly power. This isn't complicated: let parents choose from more options and watch monopoly power crumble.

Baseless Accusations

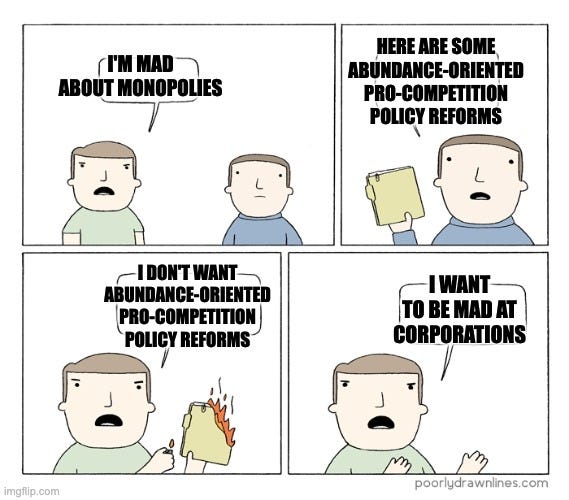

I just laid out a wide range of anti-monopoly policy reforms. I’ve written about many of them. Have the people who claim the mantle of anti-monopoly taken up any of these issues? Not as far as I can tell. What they’ve mostly done is not anti-monopoly politics so much as very selective anti-business politics. It’s basically just this meme.

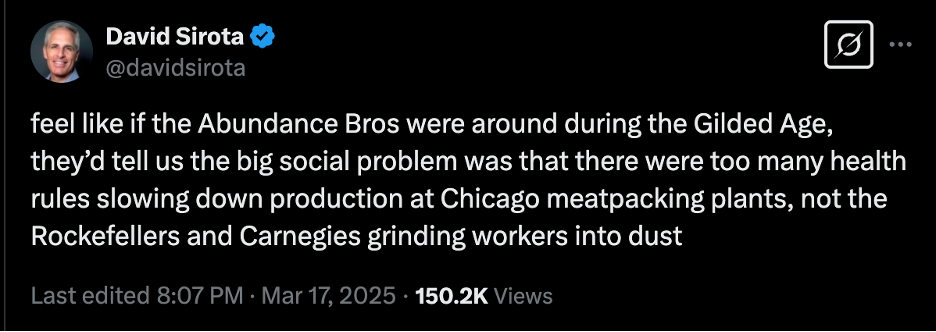

They have taken the time to write baseless accusations about what Abundance proponents “really” want. Two good examples from this genre are these two tweets by David Sirota.

It's a flat-out lie that Abundance proponents don’t care about healthcare access. A whole section of our cost-of-living agenda was about healthcare, including a section on more antitrust enforcement on hospital mergers. We have another argument for Medicare For Kids and we praised Medicare negotiating drug prices. Niskanen has written extensively about healthcare. Healthcare was Ezra Klein’s main policy beat for years. Sirota’s claim is in line with others who who argue that Abundance proponents are against redistribution. This is another baseless lie, as Derek Thompson points out.

Sirota’s second tweet says that we don’t care about antitrust or workers in meatpacking. I argued the exact opposite of what he is accusing us of. I have publicly argued for more antitrust enforcement in meatpacking. There is strong evidence that we have severe antitrust problems in a number of agricultural markets and that policy in that area badly needs beefing up (pun very much intended). I also praised the FTC’s moves against noncompete agreements.

So on one side, we have Abundance proponents who support antitrust tools where they make sense and who have lots of ideas about how to use supply-side reforms to promote competition and reduce the cost of living. On the other side, we have certain Abundance critics who make up lies about the people they want to criticize and who ignore or excuse all kinds of competition problems in numerous areas of the economy whenever those problems don’t map onto anti-business populism.

So I ask again: will the real anti-monopolists please stand up?

-GW

I don’t have a dog in this fight. I do have a question as I’m learning about the abundance writings: what are the specific recommendations for changing local zoning policies in order to develop more housing? What are the specific recommendations for changing environmental review? If I’m to advocate for the former, I’d appreciate some concrete ideas. Thank you!

As someone who used to work for Austin City Council I’ve seen firsthand how powerful many NIMBYs/anti-development voices can be. But seems like the tide is turning:

https://open.substack.com/pub/ryanclarkself/p/like-bathroom-door-locks-government?r=7y31d&utm_medium=ios