It has been more than 18 months after New York City implemented its sweeping short-term rental restrictions through Local Law 18 (LL18). The law effectively banned most home-sharing arrangements by requiring hosts to register with the city and live on-site during stays—rules that proved unworkable for the vast majority of listings. The data paints a clear picture: a policy that promised housing relief has instead delivered a windfall to the hotel industry while failing to make homes more affordable or available for residents.

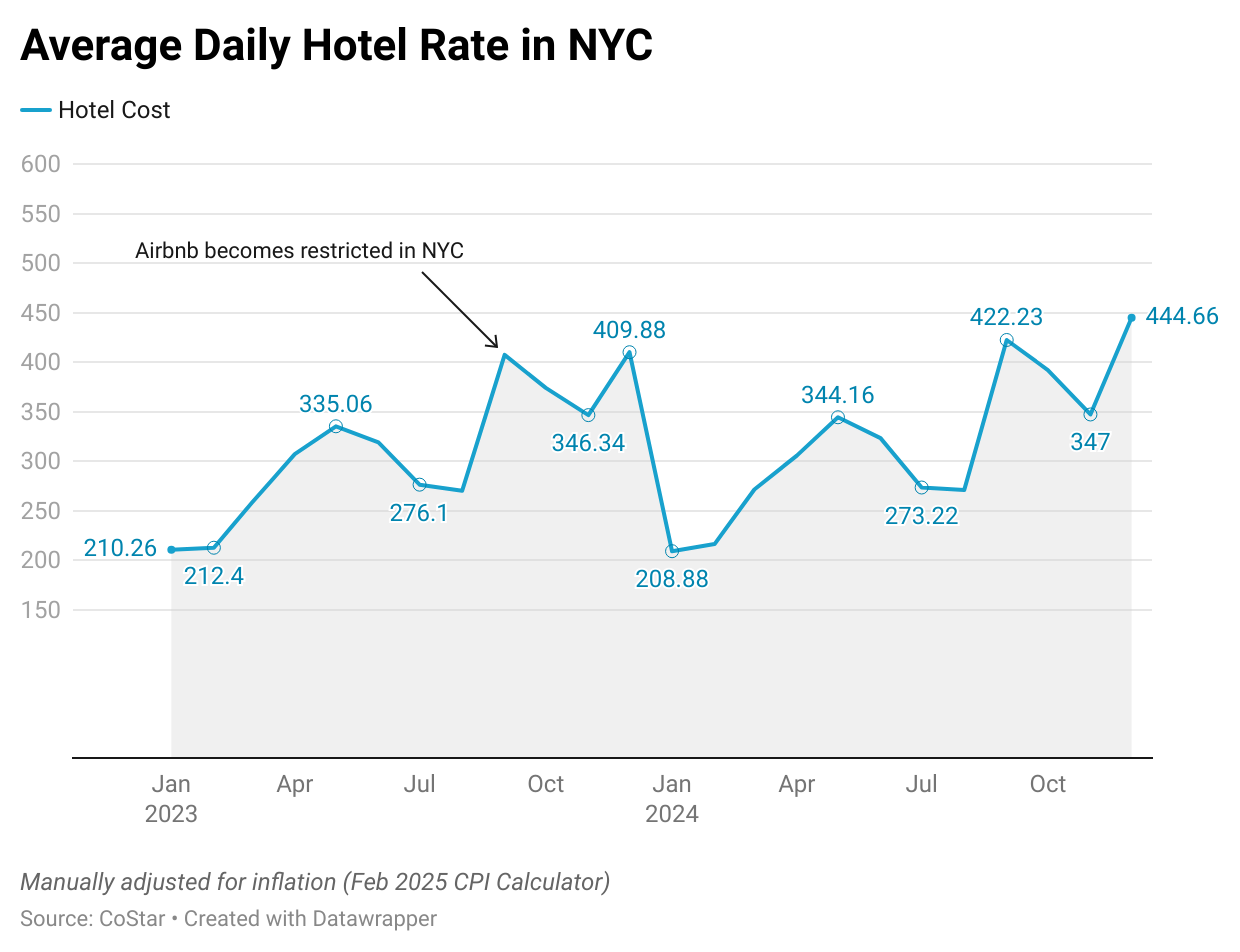

Manhattan hotel stays reached an average of $444.66 per night, adjusted for inflation based on data from CoStar, in December 2024, nearly triple the U.S. average of $150-160. This represents a staggering premium that existed even before LL18 but has widened considerably since its implementation.

The hotel industry has reaped extraordinary benefits in LL18's wake, creating a luxury accommodation market that increasingly excludes middle-class travelers. Hotel occupancy rates in NYC have surged to 84% by late 2024—effectively full capacity—compared to just 59-60% nationally. This extreme demand imbalance has fueled a pricing bonanza for hoteliers, with rates climbing 7.4% year-over-year versus the national average of just 2.1%.

LL18’s short-term rental restrictions have created a luxury-dominated hotel market, crowding out middle-class travelers and leaving New Yorkers with fewer, not more, affordable housing options.

No Relief for Housing Affordability

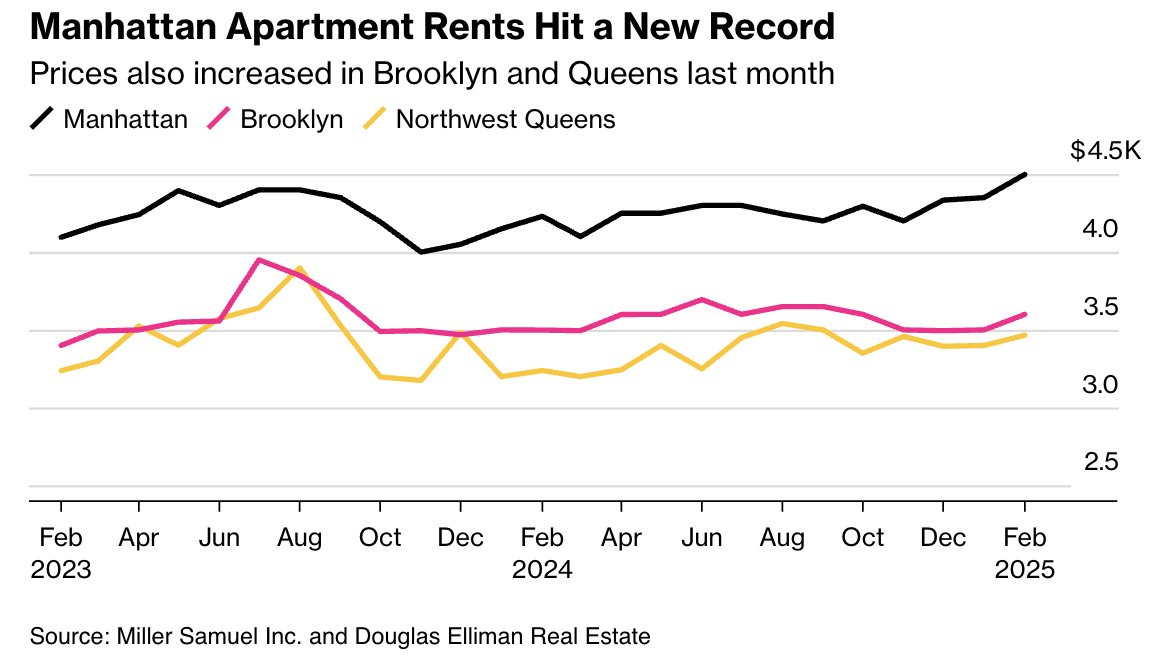

Despite promises that banning Airbnbs would ease the housing crunch, the results tell a different story. Rents have continued to soar. Manhattan apartment rents have soared to unprecedented levels, hitting a record median of $4,500 in February 2025—up 6.4% from a year earlier. Downtown Manhattan median asking rents have reached a historic $5,000/month for the first time in 2024. Bidding wars have become increasingly common, with nearly 27% of new leases signed after bidding wars—a record share. Even in the outer boroughs, prices continue climbing, with Brooklyn's median rent at $3,600 (up 2.9%) and Queens at $3,466 (up 7%).

Image Credit: Bloomberg

The city's rental vacancy rate remains stubbornly low at around 3.4%, far below the national average of approximately 6% and significantly lower than comparable cities. With over one-third of NYC renters now paying more than 50% of their income on rent, affordability metrics have worsened. The Mayor's Office of Special Enforcement noted that only about 1,400 property owners have converted short-term rentals to long-term leases—a mere drop in the bucket for a city with over 3.7 million housing units.

Inflation data reinforce these trends. Shelter costs are a major component of the NYC-area Consumer Price Index, and they continue to rise rapidly. As of late 2024, NYC’s shelter index was up ~6.0% year-over-year – with residential rent rising ~5–6% annually and owners’ equivalent rent +6.5%. This indicates that rental costs kept climbing faster than general inflation. The crackdown did not halt rent inflation; if anything, limited supply kept upward pressure on rents.

Meanwhile, “lodging away from home” (hotels) saw even sharper price increases. The CPI for hotel and motel stays spiked in NYC after the short-term rental restrictions. Nationwide, lodging-away-from-home costs jumped 3.7% in one month at the end of 2024 (the biggest jump in over a year).

Financial Hardship for Hosts and Businesses

Airbnb conducted a survey and found residents used short-term rental income to maintain financial stability:

62% of hosts planned to use Airbnb earnings to cover increased cost of living

44% used hosting income for necessities like food

42% said Airbnb income helped them remain in their homes

More than 10% reported the income helped prevent eviction or foreclosure

The economic reality for many hosts contradicts the narrative that Airbnb primarily benefits wealthy property investors. While commercial operators certainly existed, the ban has affected many middle-class homeowners who relied on this income stream to maintain financial stability in one of America's most expensive cities. For these residents, home-sharing represented an innovative adaptation to rising costs—using existing space more efficiently to generate income without requiring new construction. By eliminating this option, the city has removed an important financial lifeline for residents already struggling with inflation and high housing costs.

Hosts are not the only who have faced unintended negative consequences from this passage, where small business owners are also citing decreased traffic:

With the majority of hotels concentrated in Manhattan, NYC’s short-term rental rules make it difficult for Brooklyn businesses to capitalize on the full economic potential of tourism. Some local business owners, like Calvin Sennon of Canarsie’s TriniJamBK, have seen a 70% decrease in new customers. Our local economy is paying the price for Manhattan-centric legislation that did not take the outer boroughs into account.

Growing Momentum for Reform

In late 2024, a coalition of Council Members introduced Intro. 1107, which aims to provide relief specifically for small homeowners while maintaining restrictions on commercial operators.

The bill's lead sponsor, Council Member Farah Louis of Brooklyn, has made equity concerns central to her argument, noting that the current law is "particularly crucial for Black and brown homeowners...who have historically faced barriers to building and maintaining intergenerational wealth." Her district, with many Caribbean-American and African-American homeowners in southeastern Brooklyn, represents communities for whom home equity and rental income are vital financial lifelines.

The reform effort has gained significant momentum, securing eight co-sponsors, including a crucial endorsement from Council Speaker Adrienne Adams. The bill would remove one of the most onerous requirements of LL18—the "common household" rule—by allowing hosts to lock their private bedrooms or spaces when renting part of their home. It also seeks to broaden the registration process to make it accessible to more homeowners.

While initially more ambitious, the proposal was scaled back to ensure it wouldn't conflict with state law or the City Charter. Nevertheless, it represents an important shift in the Council's approach, acknowledging that responsible home-sharing in owner-occupied properties should be distinguished from the type of commercial operations that the original law aimed to curtail.

The growing support for reform among council members from the Bronx, Queens, and Brooklyn—areas with high concentrations of 1-2 family homes—reflects the disproportionate impact that LL18 has had on outer borough communities. Unlike Manhattan, where the housing stock is dominated by large apartment buildings and hotels, the outer boroughs are home to more owner-occupied properties, including modest duplexes and single-family homes. Their collective position signals a recognition that the blanket approach of LL18 swept up small homeowners alongside commercial operators, creating unintended economic hardship for thousands of New Yorkers.

The Root Causes Remain Untouched

The failure of LL18 to impact housing metrics reveals a fundamental misdiagnosis of NYC's housing problems. The city faces structural challenges including restrictive zoning, lengthy approval processes for new construction, and geographic constraints. The relatively small percentage of housing units that were being used as short-term rentals (less than 1% of the city's housing stock, according to Airbnb) couldn't meaningfully affect these larger market forces. That sliver was never large enough to meaningfully affect citywide rent prices, vacancy rates, or housing availability. Policymakers essentially targeted a visible but minor contributor to the housing crisis while avoiding more difficult but necessary reforms to increase housing supply through new construction and zoning changes. There have been small efforts like the watered down version of City of Yes — but these fall far short of even the meager 109,000 new homes originally proposed, of which only about 80,000 are expected to be built over the next 15 years.

As one homeowner put it: “We’re not wealthy people. Wealthy people don’t share their homes.”

The way forward should include not only reforms to LL18 that protect small homeowners while preventing commercial abuse but also a comprehensive housing strategy that increases supply across all boroughs and price points. A candidate for the upcoming mayoral campaign who understands this very notion would be Zellnor Myrie, whose recent write-up by Ben Krauss is worth reading. The city's economic vitality and cultural diversity depend on housing policies that work as intended, not symbolic gestures that ultimately harm the very communities they aim to protect.

As the City Council weighs reforms, it must acknowledge a simple truth: effective housing policy requires addressing root causes, not convenient scapegoats. We cannot continue to allow our cities to focus on short-sighted policies like LL18 to attempt to try and solve our housing crisis, instead of simply building our way out of it.

I’m neither in favor of these bans nor an expert on ny real estate, etc, but to my eyes it looks like a case could be made that non-manhattan rents were relatively stable. I can see that they rose a little, but if that’s wrong it might be worth a bit more explanation or context.