On April 17th, the U.S. Trade Representative's (USTR) office is expected to impose substantial fees on Chinese-built vessels, originally estimated at up to $1.5 million per port call for ships made in China and up to $1 million if an ocean carrier owns even a single Chinese-built vessel. This represents one of the most significant shifts in American maritime policy since the Jones Act of 1920, not only because of its scale but because it represents a fundamental shift in scope. Unlike the Jones Act, which regulates trade between U.S. ports, this proposal aims to control, through hefty fees, which ships can access the U.S. market at all.

The Trump administration is clearly putting the cart before the horse - imposing punitive measures on an industry where the U.S. has virtually no competitive presence, rather than first developing the capabilities needed to fill the gap. While framed as bold industrial policy aimed at revitalizing domestic shipbuilding and countering China's maritime dominance, the proposal has sparked widespread concern across sectors from agriculture to automakers. Bill Hanvey, president and CEO of Auto Care Association, stated, “The proposed ship fees would cause economic harm by disrupting critical logistics networks, undermine the competitiveness of US businesses and increase prices for American consumers.”

While this might sound like a fight between bureaucrats and cargo carriers, the real impact will land squarely on regular Americans, with higher prices at the store, fewer U.S. exports, and potential job losses in port cities and factory towns.

The Shipbuilding Reality Gap

This latest move risks further isolating America in a sector where we already severely lag behind global competitors. The U.S. holds just 0.10% of total gross tonnage (overall size and capacity of the ship), compared to Asia, which dominates the current maritime shipping industry with China leading at 51%.

Image Credit: World Capitalist

Though some modifications to the original plan are now under consideration, this proposal could reshape U.S. port access, raise consumer prices, and weaken exporters' competitiveness, all in pursuit of reviving a long-dormant shipbuilding sector.

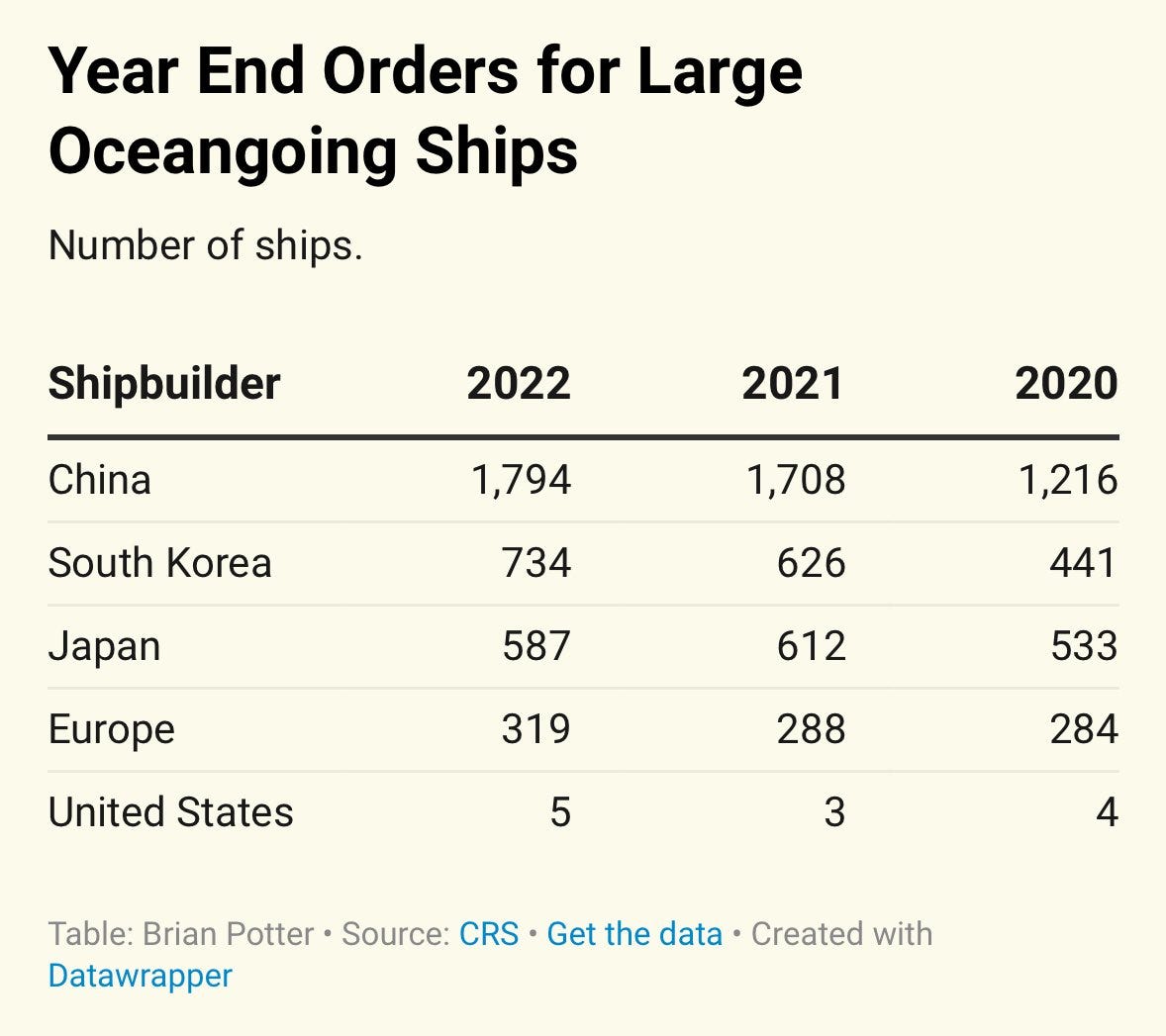

A fundamental challenge for the USTR proposal is the vast disparity between U.S. and global shipbuilding capabilities, as illustrated in the following data:

Image Credit: Construction Physics

In 2022, China produced 1,794 large oceangoing vessels compared to just 5 for the United States. In fact, China constructed more ships in a single year than the U.S. has in decades. The U.S. also has built zero container ships in 2024 despite them being the backbone of global trade.

These Jones Act ships tend to be old and significantly smaller than modern global trading ships - a typical Jones Act container ship might carry 1,000-3,000 TEUs (twenty-foot containers), whereas cutting-edge international ships carry 15,000-24,000 TEUs. This gap highlights why the Jones Act has failed to generate a robust shipbuilding industry despite a century of protectionism: by shielding U.S. shipyards from foreign competition, it removed the pressure to innovate, cut costs, or scale up.

American-made vessels cost 5-8 times more per capacity ton than their Chinese counterparts. As Petersen puts it, ‘an American-made 3,000 TEU container ship costs roughly the same as a 24,000 TEU megaship built in China’ — an 8x disparity that underscores the structural gap.

Given these realities, the requirement to have 15% of exports on U.S.-flag ships (and 5% on U.S.-built ships) within 7-8 years appears extraordinarily ambitious, if not completely infeasible. The policy seems to be trying to conjure an industry through regulatory mandates rather than addressing fundamental competitiveness issues.

The Proposed Fees: Another Layer of Protectionism

The USTR's original proposal, outlined a sweeping fee structure targeting Chinese-built and Chinese-affiliated vessels:

Up to $1.5 million per port call for ships constructed in China

$500,000-$1 million per call for carriers owning even a single Chinese-built vessel

$1 million per call for Chinese state-owned shipping companies

Initially, maritime experts warned these fees could potentially "stack," with combined charges reaching up to $3.5 million per U.S. port visit for vessels meeting multiple criteria. However, in recent developments, U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer told a Senate Finance Committee hearing that "not all of the agency's proposed multimillion-dollar fees will be implemented and may not be cumulative," explicitly stating that "they're not all going to be stacked."

The Trump administration is now considering significant modifications to the plan after receiving what Reuters described as "a flood of negative feedback from industries." Among the changes under consideration are:

Delayed implementation timelines

Adjusted fee structures based on the percentage of Chinese-built ships in a company's fleet

Tonnage-based fees instead of flat rates, which would reduce the burden on smaller vessels

Tonnage-based fees instead of flat rates, which would reduce the burden on smaller vessels. Larger ships with higher tonnage ratings can transport more cargo and generate more revenue per voyage, making a tonnage-based fee structure more proportional to a vessel's earning potential than a one-size-fits-all flat rate.

These potential adjustments reflect the realization that the original proposal was formulated primarily with large container ships in mind, without fully considering the impact on commodity flows and other shipping segments. However, despite Greer's testimony and reports of possible modifications, no official changes have been announced or confirmed as of mid-April. This ongoing uncertainty is adding yet another layer of unpredictability to an already volatile trade environment, forcing shipping companies to make operational decisions based on conflicting signals and speculation.

The situation exemplifies a troubling pattern in recent trade policy where industries must navigate not just new restrictions, but also the ambiguity surrounding their final form and implementation. Nevertheless, as Jefferies analyst Omar Nokta noted, "all shipping segments would be affected, given the level of disruption likely to take place as operators shift vessels to minimize exposure to U.S. fees.”

Beyond these immediate fees, the proposal also established a phased requirement that an increasing percentage of U.S. exports (reaching 15% by the eighth year) must be transported on American-flagged vessels, with a subset requiring U.S.-built ships.

This approach effectively expands the protectionist principles of the Jones Act - which for over a century has required that all goods transported between U.S. ports be carried on American-built, owned, and crewed vessels - into the realm of international shipping.

Economic and Logistical Implications

Industry analysts have warned about several disruptive consequences if the original proposal is implemented:

Major/Minor Port Imbalance: According to Flexport CEO Ryan Petersen, shipping companies are already indicating they would concentrate their calls at major coastal hubs while bypassing smaller regional ports to reduce their exposure to these fees.

Supply Chain Bottlenecks: This artificial concentration of cargo volume would likely overwhelm the infrastructure at ports like Los Angeles/Long Beach, potentially recreating the congestion issues experienced potentially recreating the severe congestion experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Such bottlenecks can lead to ripple effects across the supply chain, including delayed shipments, increased transportation costs, and shortages of goods on store shelves.

For businesses, especially those reliant on seasonal inventory, these disruptions can result in missed sales opportunities and excess unsold stock. Consumers may face higher prices and limited product availability, as seen during the pandemic-induced supply chain crisis.

International Port Diversion: Both importers and exporters may seek alternative routes through neighboring countries, creating inefficiencies and potentially causing permanent shifts in established trade patterns.

Cascading Cost Increases: The combination of direct fees, longer inland transportation routes, and supply chain delays would ultimately increase costs throughout U.S. supply chains, affecting both consumer prices and export competitiveness.

Exporters rely on affordable, reliable shipping to get their goods to global markets. If fewer ships serve U.S. ports, or if costs surge due to new fees, American goods become more expensive or harder to deliver abroad, making them less attractive to foreign buyers.

Early Market Disruption Already Visible

Recent shipping data provides compelling evidence that the market is already reacting dramatically to the pending USTR decision, within the broader context of escalating protectionist policies. According to Vizion maritime analytics, the week of April 1-8, 2025, saw catastrophic week-over-week declines when compared to the previous week:

Image credit: Vizion

These figures suggest that the shipping fees proposal, coming on the heels of other sudden volatile tariff announcements, is creating a perfect storm for U.S. trade. The extreme volatility in trade flows demonstrates the real-world consequences of unpredictable protectionist policies. While the USTR's proposed fees on Chinese vessels are intended to support domestic shipbuilding, they appear to be contributing to a broader trade contraction that threatens to undermine U.S. export competitiveness and supply chain stability.

Rethinking Maritime Protectionism

The USTR proposal represents an attempt to extend Jones Act-style protectionism to international shipping at a time when there's growing recognition that such measures often create more economic harm than benefit. The proposed means risk significant collateral damage to U.S. ports, exporters, importers, and ultimately consumers.

The apparent reconsideration of certain aspects of the proposal is a positive development, suggesting an understanding that blunt protectionist tools may not achieve the desired outcomes. However, the fundamental question remains whether any version of these fees can meaningfully address the enormous competitive gap between U.S. and Chinese shipbuilding without imposing disproportionate costs on the broader economy.

Rather than expanding Jones Act principles to international trade, policymakers might more productively focus on investments in port infrastructure, automation technology, and workforce skills - measures that would improve efficiency and competitiveness without imposing new constraints and costs on an already complex global shipping environment.