Delivering Rural Healthcare

Democrats need to do better by rural America and compete better in rural America. It is that simple.

Democrats face a rural emergency. Of America's 3,111 counties, half the 2024 presidential vote came from the 150 largest. In the other half, the remaining 2,961 counties, Harris lost badly (39.6% to 58.6%), winning only 350 of those counties. These results are not unique to Harris; they mirror results from 2020 and 2016. As long as Democrats do this poorly in rural America, we will struggle to control the Senate and remain at a severe disadvantage in presidential and statewide races.

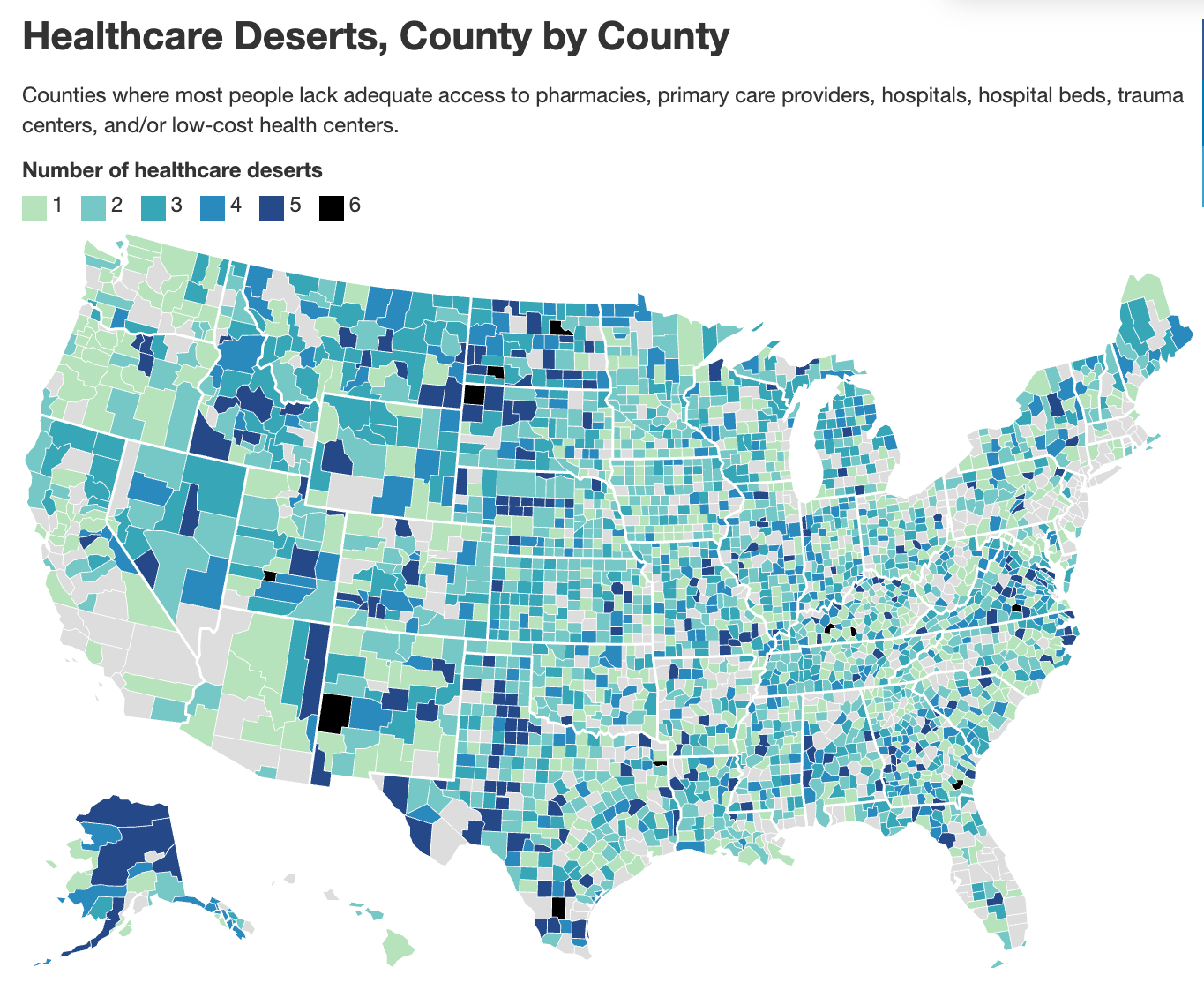

And it goes without saying that helping rural America is correct on the merits too, which is why I’ve argued that Democrats should champion policies like promoting resource extraction industries such as mining, like encouraging mass timber, like removing the chassis rule, and like facilitating permitting reform. But the area I want to focus on today is healthcare. To put it directly, healthcare is too hard to access and too expensive for rural Americans. Here’s how we can do better.

Workforce Reforms: Who Provides the Care?

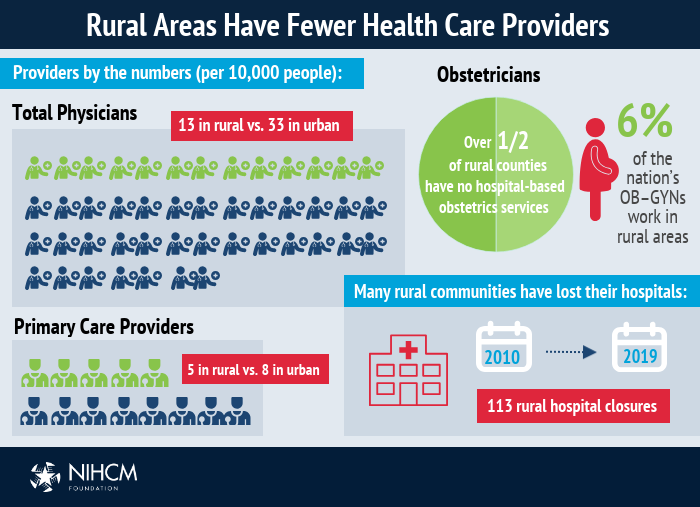

Rural America has a healthcare workforce shortage. 65% of rural counties do not have enough primary care physicians. Rural areas struggle to attract healthcare providers. About 20% of Americans live in rural counties but only 9% of physicians do. This is especially problematic because rural America is older, poorer, and sicker than its urban and suburban counterparts.

So, the first step to improving rural healthcare access is addressing the workforce shortage through creative solutions that expand the supply of qualified providers. This includes foreign-trained doctors, non-physician practitioners working at their full scope of practice, and cross-state licensing reform.

First, following Tennessee's new law that went into effect last year, states should reform licensing requirements for foreign-trained doctors. These experienced physicians have already completed medical education and training abroad but are forced to repeat residency programs in the US, often pushing them into non-medical careers. By granting provisional licenses to international medical graduates who pass the same standardized exams as U.S. doctors, we could quickly expand the healthcare workforce.

A way to accelerate this program’s growth would be through Heartland Visas, which are place-based visas that would offer expedited permanent residency for professionals who commit to living in participating counties for a set period. The dual opt-in model ensures both communities and visa holders choose each other, increasing the likelihood of long-term retention. This form of immigration is politically popular too; 74% of Americans think immigrants increasing the number of doctors and nurses in their area would be a good thing whereas just 6% oppose it.

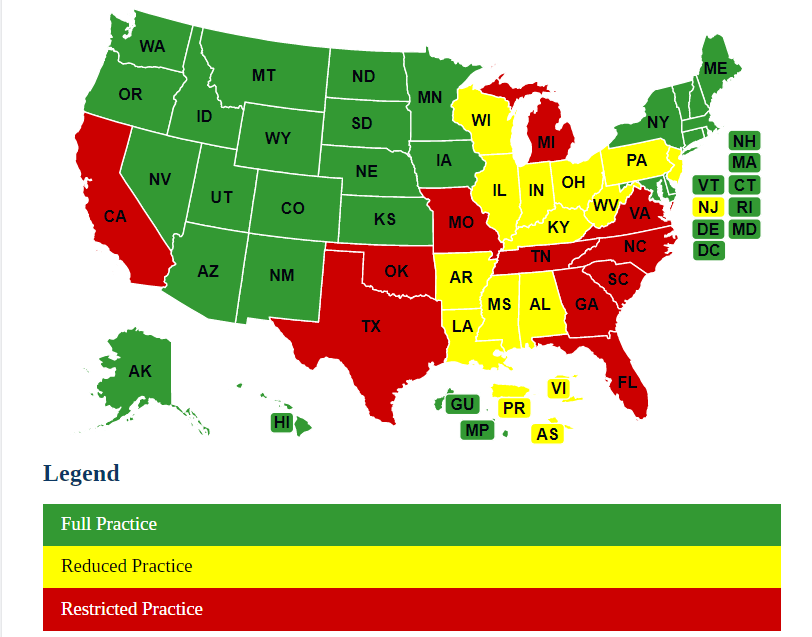

Another way to compensate for the shortage of doctors in rural areas would be to expand the scope of practice for physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and pharmacists. These providers can perform many primary care services at lower costs than physicians while maintaining quality outcomes. By allowing them to practice at the full extent of their training, rural areas could gain immediate access to care without the lengthy wait for doctor recruitment. These professionals are also more likely to move to and stay in rural communities than physicians. The cost benefits are substantial too. Studies show nurse practitioners and PAs can provide comparable care at significantly lower cost, helping rural hospitals maintain financial sustainability while improving healthcare access.

Another problem is that state-specific licensing requirements create artificial barriers for healthcare delivery, particularly in rural areas near state borders. One way to alleviate that would be to have greater interstate licensure recognition, which would allow providers to practice across state lines without obtaining multiple costly licenses. This flexibility is especially valuable for rural communities, which could access providers from neighboring states' metropolitan areas through telemedicine or part-time in-person arrangements.

Locational Reforms: Where Does the Care Get Done?

It is harder to make delivering healthcare cost effective in lower population density places, particularly for hospitals. Between 2010 and 2021, 136 rural hospitals closed. 700 more, a third of all rural hospitals, are in danger of closing in the near future. For access and cost reasons, it is vital that we strategically shift where and how healthcare services are delivered by moving from traditional inpatient to outpatient settings, expanding hospital-at-home programs, and removing regulatory barriers to competition.

Shifting care delivery from inpatient to outpatient settings is one of the most promising approaches for sustaining rural healthcare. Rural hospitals often struggle to maintain financially unsustainable inpatient capacity. By focusing resources on outpatient care, facilities can expand service hours, lower costs, and reduce wait times. Medicare's Rural Emergency Hospital designation now provides similar opportunities nationwide, offering enhanced reimbursement for rural facilities that maintain emergency and outpatient services without inpatient beds. This can hopefully save hundreds of those at-risk rural hospitals from having to close.

Hospital-at-home programs can extend the outpatient care model further by delivering acute care services directly in patients' homes. These programs provide hospital-level care through a combination of in-person visits, remote monitoring, and telehealth, reducing costs by 30% while improving outcomes and patient satisfaction. Rural communities could particularly benefit from this as patients avoid lengthy travel for hospitalization.

Here’s the problem. These innovative programs can only exist because of a government waiver, which just so happens to be set to expire on September 30th of this year. In the previous Congress (2023-2024), Democrats sponsored legislation, the “Hospital Inpatient Services Modernization Act” which would extend this waiver through 2029. That bill was not passed, perhaps because the expiration was past the window of that Congress and so it was easy to kick the can down the road. But it is 2025 now. The clock is ticking and September 30th will get here very soon. Congress needs to pass a waiver extension as soon as possible.

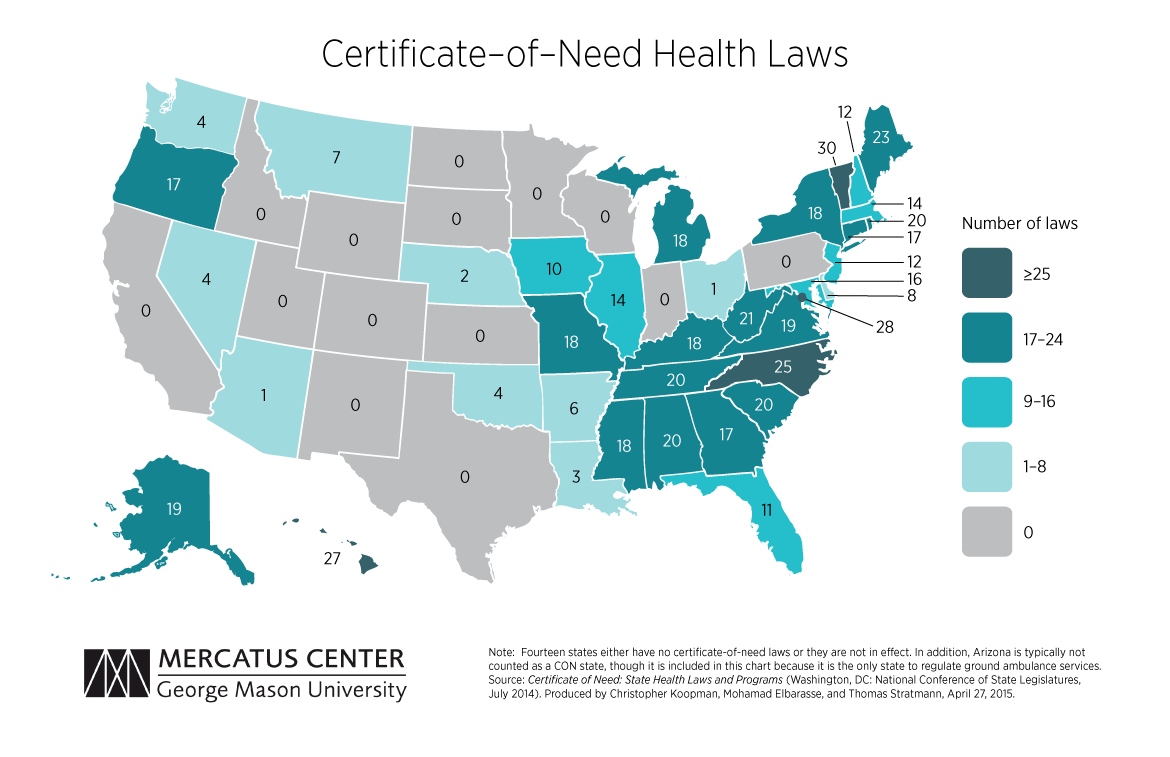

Finally, certificate-of-need laws disproportionately harm rural healthcare by restricting competition and new service development in areas that already struggle with provider shortages. Research consistently shows that CON laws undermine access and raise costs in rural communities. Compared to states without CON laws, states with CON laws have 30% fewer rural hospitals, higher variable costs in general acute hospitals, higher Medicaid costs for home health services, higher per admission hospital expenditures, uninsured patients having to pay more out-of-pocket, and higher expenditures per resident in nursing homes.

Pricing Reforms: How to Increase Transparency and Lower Costs

Pricing mechanisms are key to making rural healthcare more affordable while also being financially sustainable. Two reforms could help here: reference-based pricing and all-payer claims databases.

Here is how reference-based pricing works. It’s a payment model where a payer (like a state employee health plan for example) establishes standardized maximum reimbursement levels for healthcare services based on a benchmark rate, usually some percentage of what Medicare pays for the same service. This helps keep premiums from rising too much, makes revenue more predictable for providers, and increases price transparency. This is not some purely theoretical idea. Both Oregon and Montana has saved tens of millions of dollars by implementing reference-based pricing.

All-payer claims databases (APCD) collect claims data from all payers (commercial insurers, Medicaid, and Medicare) in a standardized format in a standardized format, hence the name, and so provide further price transparency that empowers rural healthcare stakeholders to identify price variations and negotiate more effectively. 18 states currently have APCDs. The rest should follow suit.

Abundance is for Rural America Too

This newsletter and its focus on cost of living is obviously a part of the broader Abundance Agenda framework. Contrary to what some may say, we are not concerned only with the problems of blue cities and blue states. Those matter, of course. But rural America experiences scarcities and too-high costs too. They may not have the same housing challenges as California or Massachusetts, but they have other challenges, perhaps none more important than in healthcare. We can do something about that. We are Americans and we can all rise together.

That’s what we’re in the business of arguing for in this newsletter: more good things, for everyone, Rural America too.

-GW