There’s a maddening dynamic going on in California housing policy. Yes, I know that is a ‘only happens on days that ending in Y’ problem, but this one is particularly illuminating.

California voters rate the high cost of housing as their top concern. It’s a big reason why California moved to the right in November’s election. The state’s political leadership is hearing loud and clear that housing is what voters want them to fix. Both legislative leaders have said that reducing the cost-of-living is their top concern.

And yet…the state Senate just named Aisha Wahab the chair of the California Senate Housing Committee, which basically makes her the gate-keeper for any housing reform that might go through the state legislature. She’s anti-development, skeptical of reducing parking mandates, doesn’t believe that lowering costs for developers translates into lower rents and purchases, and wants to “protect our supply” and “curb the demand” for California housing. Those are not gotchas or regretted verbal fumbles. That’s from her own Instagram!

How is a California NIMBY with these views going to increase housing supply? How do we explain the paradox of her being put in this position? The easy answer is hypocrisy, but I don’t think it’s that. California’s housing shortage is, in large part, due to an incredible addiction to anti-development policies that are momentarily comforting, but in the long term self-destructive.

I don’t use the addiction analogy here to belittle addiction but rather to underscore the seriousness and nature of California’s problem. Addictions are psychologically powerful things. They override rationality and keep people stuck in cycles of self-harm even the people caught up in them want to stop. Ingrained habits die hard. Thought patterns are not easily changed. And the call of the thing that soothes refuses to fade quietly into the night.

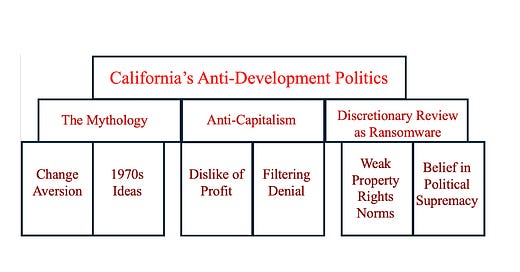

Californian political thought around housing can’t seem to let go of three ideas: (1) a purity mythology, (2) an anti-capitalist streak, and (3) a deep-seated instinct to use discretionary review as a kind of ransomware. Fixing California’s housing problem requires breaking all these addictions, but a good place to start is hiring a better Housing Chair.

The Mythology

California's housing is trapped in a mythology forged in the 1970s, a time when environmentalism was first taking hold. There's a pervasive belief among many long-time California residents that the state reached its ideal form precisely when they arrived. This mythology manifests as a profound change aversion and a conviction that any alteration to the existing neighborhood character represents a degradation of what makes California special.

This nostalgia-tinged worldview ignores the reality that California has always been defined by growth and reinvention. NIMBYs often invoke environmental protection as justification for opposing development, but this represents a misapplication of 1970s environmentalism that raised emissions via forcing people into longer commutes even as it kept certain people’s views from changing. The "protect what we have" mentality treats California as a museum piece rather than a living community, even when doing so creates more environmental damage than it prevents.

The comfort this mythology provides is immediate: it allows existing homeowners to maintain their neighborhood aesthetic and property values, and feel good about their stewardship of The Way Things Have Always Been. But the long-term harm is devastating. By preventing housing construction, this mythology prices out younger generations from the communities their parents could afford. Residents often vote with their feet – and California is the poster child of residential flight to more affordable states; fully a third of Californians say that they are considering moving out of the state due to high housing costs.

Anti-Capitalism: Power, Profit, and Filtering

California's crisis is exacerbated by a deeply ingrained anti-capitalist streak.

There's a peculiar worldview that treats housing differently from every other product or service and sees profit in housing development as inherently exploitative rather than as the economic engine that could solve the very shortage driving up costs.

This anti-profit attitude manifests in a fundamental misunderstanding of how housing markets function. In virtually every other market, we understand that more supply leads to lower prices. Yet when it comes to housing, many California politicians reject this basic economic principle. They insist, as Senator Wahab does, that "lowering costs for developers doesn't translate into lower rents and purchases." This denial of economic reality provides a comforting narrative for some on the left – maybe we can solve the housing crisis without allowing developers to make money? Good luck.

Part of this view emerges from an insistence that the class politics in housing are different from what they actually are. Lots of people, particularly those with more socialist and populist leanings, think about power in a political economy lens, i.e. “who has power?” And that’s fair. But another way to think about power relevant to housing is, “what kind of power do people have?”

“Go power” (the power to build new housing) and “stop power” (the power to block new housing) do not sit neatly along social class lines. Developers and landlords are often both affluent to rich, but one wants more Go Power and the other wants more Stop Power. Renters and incumbent homeowners sit oddly in terms of social class too. This is why Left-NIMBYs hate thinking this way. Social class struggle is one of the centerpieces of their worldview. They truly, deeply want the story to break down along bad rich people (capital) versus good working class and poor people (labor) lines. But it doesn’t. This is not to say that class plays no role in housing politics. It most certainly does. Much of suburbia’s excessive zoning is built on a foundation of class snobbery. Much of the anti-gentrification discourse hosts a deep resentment toward professional class newcomers.

But the central thing to understand about new housing is that when Go Power wins over Stop Power, it helps everyone. When developers build new housing, supply will lower prices everywhere. . It’s a process called filtering, and it works like this. When new housing is built, it creates a chain reaction of benefits throughout the market. A new $800,000 home may not directly help a middle-class family, but when someone vacates their $600,000 home to move into that new construction, they create an opportunity for a family that couldn't afford the more expensive home. This cascade continues, opening opportunities at every price point.

Studies from the American Economic Review and the Federal Reserve confirm this filtering effect. You can find more of those studies here, here, and here. And there are more besides those. When "go power" wins, when new construction is permitted, renters gain leverage as they have more options. Supply created by profit-seeking developers actually strengthens renter and buyer power against landlords by increasing competition. This is one of the reasons why Abundance is the Real Anti-Monopoly politics.

The harm in this anti-capitalist addiction is substantial. By demonizing developers and profits, California hamstrings the most vital mechanism that could most effectively address its housing shortage: more supply. This ideological stance means less housing gets built, prices remain high, and people suffer, all while activists and politicians get to feel the emotional high of congratulating themselves for "protecting" communities from "greedy developers."

Discretionary Review as Ransomware

The third pernicious addiction California's housing market suffers from is treating discretionary review as a form of economic ransomware. In case you haven’t had to deal with it, ransomware is when a company is going about its business providing goods or services and all of a sudden experiences a cyber attack in which the attackers refuse to let the company continue with its operations until they have paid some amount of ransom to the attackers. This is what certain community groups seek to do to developers.

When a developer proposes new housing in California, the default response isn't excitement about addressing shortages, but rather "what can we extract from this developer before granting permission?" This ransomware mentality treats every building permit as an opportunity for a shakedown. Local governments and neighborhood groups act as if they're doing developers a favor by allowing them to exercise basic property rights, rather than seeing developers as bringing valuable growth to the community. This process is built on weak property right norms coupled with an inflated belief in political supremacy over market decisions. It creates a toxic, unpredictable environment for housing development.

The momentary comfort this provides is clear, it gives neighborhood groups and local officials a feeling of control and the satisfaction of extracting concessions. It validates their belief that they, not markets or property rights, should dictate what gets built. But the harm is devastating. Countless projects never materialize because developers simply avoid California's regulatory gauntlet. Others become financially unviable after being loaded down with mandates for below-market units, parking requirements, aesthetic conditions, and all manner of fees.

These are not small things. On average, California towns charge homebuilders more than $21,000 per multifamily unit and over $37,000 for a single-family house, both of which are roughly three times the national average. Inclusionary zoning, i.e. mandates for below market units, take a lot more market-rate units off the market than the number of below-market units it adds. Parking minimums significantly contribute to the fact that 34% of Riverside and 23% of Los Angeles are taken up by off-street parking.

These issues stymie otherwise good reforms. SB 9, which went into effect in 2022, would have allowed by-right duplexes but has been hamstrung by localities adding intentionally onerous design requirements, among other maneuvers designed to sandbag new housing. Because of excessive labor requirements and lack of by-right approval, SB 6 —which would have created more housing via mixed use zoning- had no uptake at all. Market rate developers wanting to take advantage of AB 2011 —which would have created more housing along commercial corridors— were “deterred by affordability requirements, prevailing wage mandates, [and] reciprocal easement agreements.”

This mindset has created a permission-slip society where even modest development requires navigating years of hearings, environmental reviews, and arbitrary demands from anyone with the desire to say "no." The result is predictable: chronic housing shortages, outmigration of young families and businesses, increased homelessness, and higher taxes to address problems created by the very policies meant to "protect" communities.

Breaking Away From ‘Yes, But Only If’ Housing Policy

Yes to new housing but only if it changes nothing, and only if no one profits from building it, and only if the developer pay’s a king’s ransom in concessions to be allowed to build it is a recipe for no new housing. It’s a tragicomical example of refusing to accept that tradeoffs are real.

This is how the process of building permits became so byzantine and arduous that in the 75 days after the Palisades fire, LA only approved four new permits to rebuild burned homes. California’s housing problem won’t and can’t be fixed overnight. But some good first steps would be to pass SB 79 (which would tailor zoning near qualifying transit stops), SB 677 (which would make improvements SB 9 that was about by-right duplexes), and SB 607 (which would make targeted reforms to CEQA), and AB 609 (which would exempt infill housing from CEQA). Another would be to get a better chair of the Senate housing committee.

Aisha Wahab as gatekeeper to housing reform is potentially a disaster, but this is about more than Aisha. This about a state that’s telling college students to sleep in their cars but can’t break its addiction to change aversion, a state can be home to some of the world’s most important companies but can’t break free of seeing capitalism as the problem rather than the solution, a state where whole zip codes are million dollar plus homes only but can’t free itself from processes that are little more than ransomware shakedowns.

Like other addictions, these ideas may feel good in the moment, but they pave a road to self-sabotage and pain. Like other addictions, admitting the problem is the first step to recovery. And like other addictions, to break them, you actually have to be committed to breaking them.

-GW